#InConversation with Sabiha Dohadwala

By Sanjana Srinivasan | Apr 18 2023 · 8 min. read

Sabiha Dohadwala's solo online viewing room, PERCOLATE, presents her artistic practice over the past six years. A Mumbai-based textile artist, Dohadwala's work broadly consists of personal responses to particular places, spaces, and memories of them. Sanjana Srinivasan speaks to Sabiha about her work, inspirations, and the future.

Sanjana - Hi Sabiha! Taking off from what is covered in your solo Online Viewing Room (OVR), PERCOLATE, I’d like to begin by asking you about ideas of erasure and preservation that are inherent in your practice. While there has been a drastic shift in your visual language, I still think you are working with notions of erasure and the idea of preserving places, spaces and the feelings they evoke in you. Could you elaborate on this?

Sabiha - Throughout history, humans have been driven to record their experiences and the passing of time. However, the records we have are often from a narrow perspective, resulting in the loss of valuable narratives. I endeavour to create a personal account of my own time through the textiles I weave. Drawing on the long tradition of using textiles for record keeping (with one of the earliest examples being the quipu), I see cloth as an ideal medium for capturing memories. By using textiles in this way, I look at my work as a site of storytelling, documenting our lives and the histories we leave behind. I believe that memory is what is constantly influencing us. What we choose to remember shapes our narratives, it gives us a sense of belonging, it helps anchor ourselves to a certain place in time.

I want my work to capture the way in which we experience the world, how we move around within and understand it. I hope to convey how personal memories could also be a very collective experience.

Sanjana - How does the method of weaving in particular help with the idea of preservation?

Sabiha - Weaving is an emotional act. It has been used for centuries to create a record of people’s lives. Motifs on old textiles give us access to beliefs, lifestyles and surroundings of the people who created the cloth. By using this technique, my artworks become a form of preservation in and of themselves, as they can act as a record of specific memories, experiences, and cultural histories.

Weaving is also meditative. A weaver sits on the loom and develops a rhythm with the machine; the body and loom work in harmony. The process allows me to connect with my memories and experiences on a deeper level. This act of reflection and contemplation is a form of preservation in and of itself, as it helps me to remember and understand the experiences that I am trying to capture in my work.

This is what drew me to the medium. It helped me feel as though I could embed my memories into cloth and pass them on.

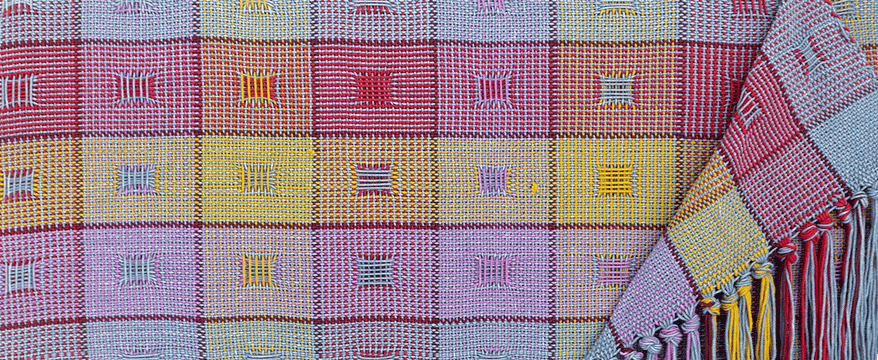

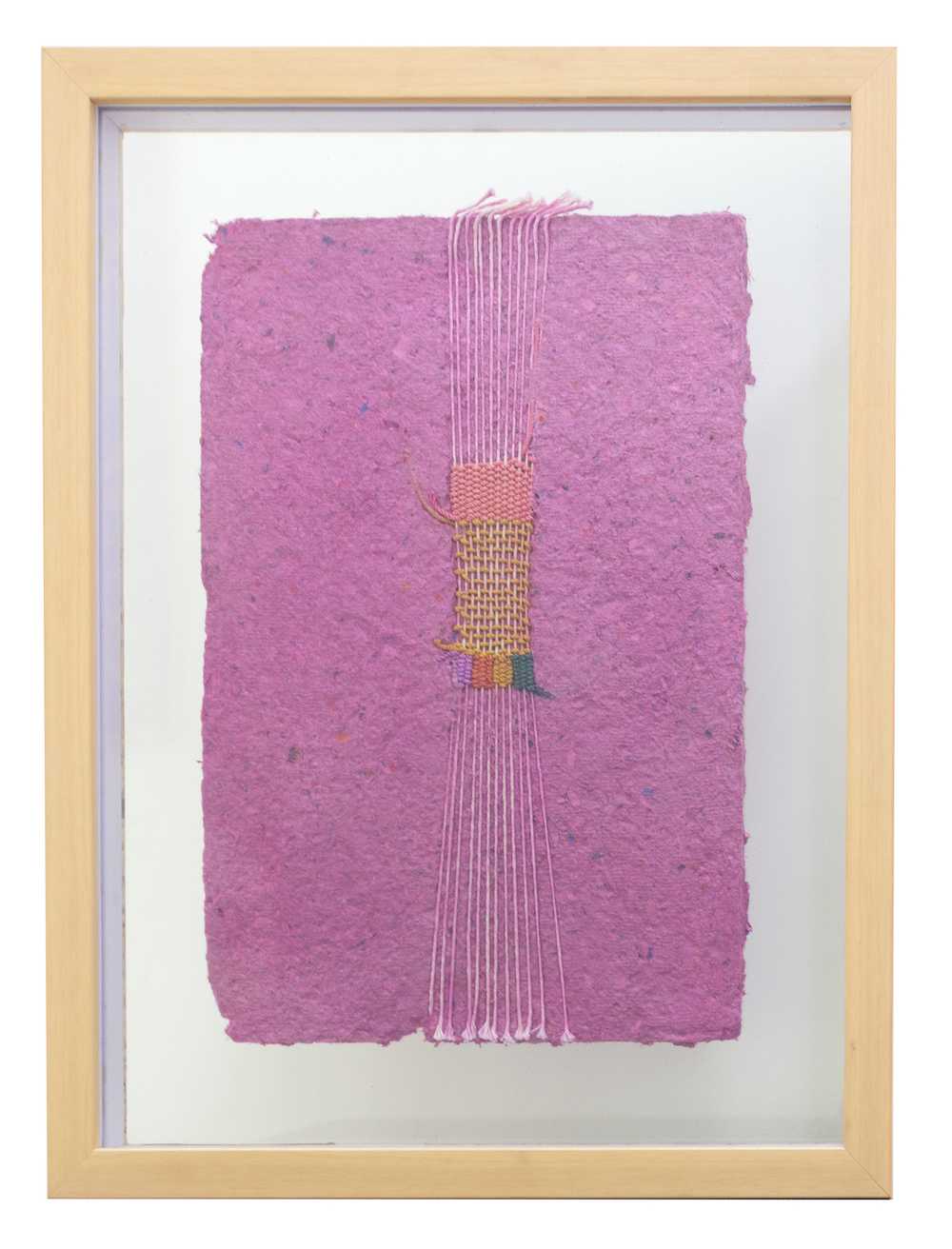

Severed, 2018

Sanjana - Could you speak more about the innovative shapes, forms and styles in which many of your ideas come together? Most of the time, your artworks are three dimensional too—even from 6 years ago when you made Severed.

Sabiha - As a textile artist, I am interested in exploring the possibilities of the medium beyond the traditional two-dimensional plane of the cloth. While weaving, threads are always under tension so the work has a certain rigidity to it while it is being created. Once off the loom, the work takes on a more fluid quality and the appearance of the textile changes. In an attempt to explore this malleability of cloth, I started experimenting with the woven piece off the loom.

In my earlier work, Severed, I was interested in exploring the idea of fragmentation and the ways in which memories can become disjointed over time. The artwork takes the form of a three-dimensional sculpture made up of multiple layers of fabric. The work was created in layers so that the viewer could walk between them and experience each layer separately. This way of experiencing the work was an attempt to create a spatial environment for the viewer.

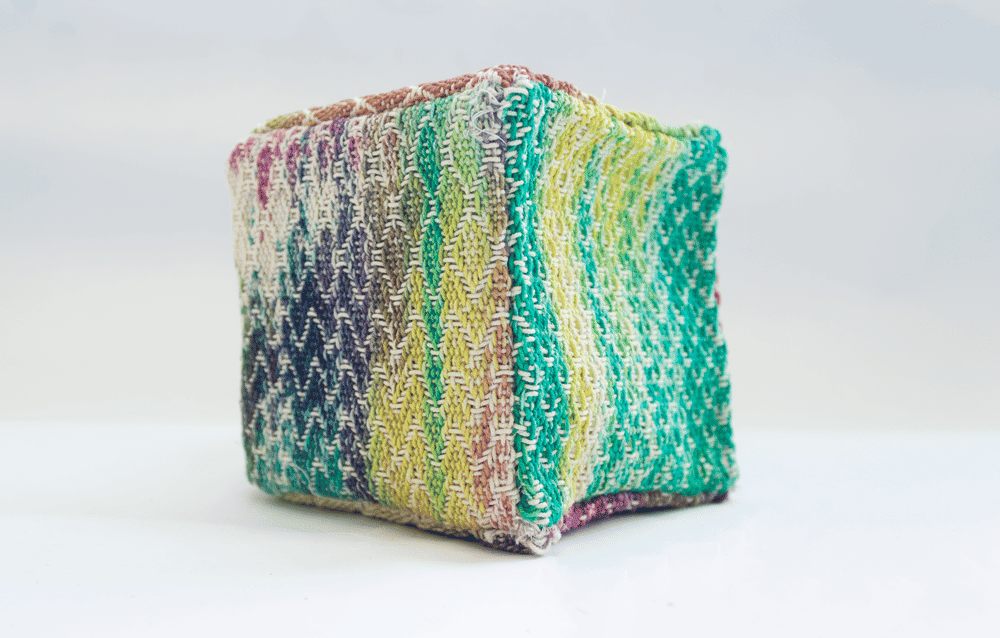

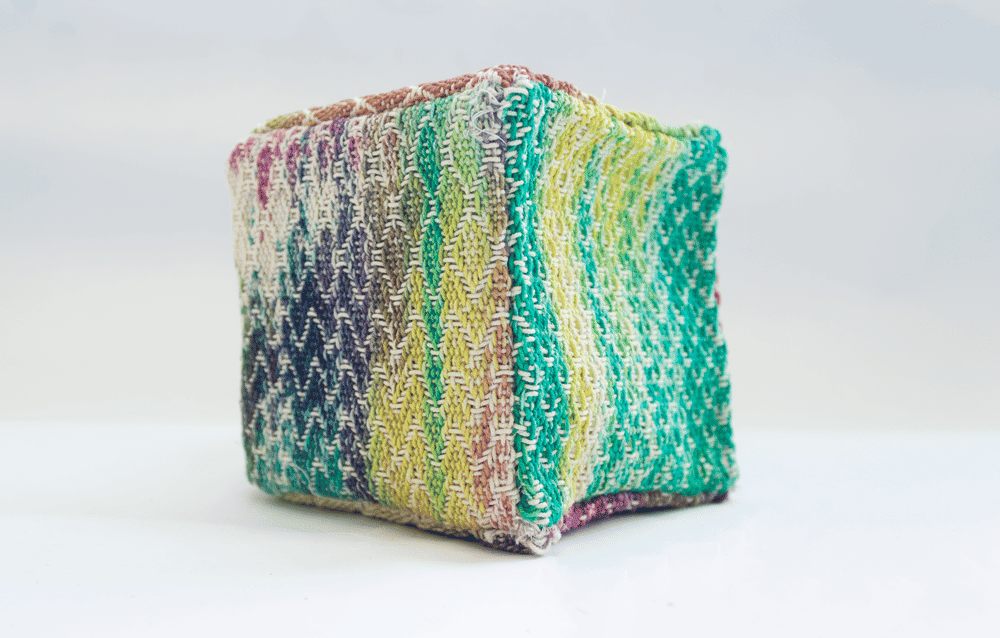

In my recent works, Flat 804 and Flat 1603, I have created three-dimensional objects from woven textile. This was a way of challenging our perception of rigid objects that we view as cold and hard surfaces and adding softness to them. In these works, the movement of cloth is a snapshot in time.

Overall, my approach to form and style is driven by a desire to push the boundaries of what is possible with textile as a medium. By experimenting with innovative shapes, forms, and styles, I am able to explore the materiality of textiles in new and exciting ways, while also conveying the emotional and conceptual ideas that underpin my practice.

Flat 804, 2023

Flat 1603, 2023

Sanjana - Speaking of innovative forms, shapes and styles, in what ways do you find the shift in visual language from an image-based one helping your practice? I know you mentioned that you were thinking about your audience and how you felt an image-based language could isolate a viewer because of their lack of familiarity with the place itself. Usually I’d think it's the opposite.

Sabiha - That's an interesting point, and I can understand why it might seem counterintuitive. However, for me, the shift away from an image-based visual language has actually been quite liberating.

When I first started working as a textile artist, I was primarily interested in capturing the details of disappearing Islamic architectural structures through my weaving. However, I began to realise that this approach was limiting in terms of the emotional impact of my work. By focusing solely on the physical structures, I was neglecting the emotional and psychological experiences that these places evoke in me and in others.

This led me to experiment with a more abstract visual language that allowed me to explore the emotional resonance of place and memory more deeply. By weaving together the warp and weft of my materials in intricate and complex patterns, I am able to create textiles that convey a sense of depth and complexity that goes beyond the surface-level details of a particular place.

In terms of my audience, I felt that an image-based language could be isolating because it relies heavily on the viewer's familiarity with the specific place being depicted. If someone is not familiar with the architecture or cultural references in the image, they may feel excluded or disconnected from the work. By contrast, an abstract visual language allows for a more universal emotional connection between the artwork and the viewer. Even if someone has never been to the specific place that inspired my work, they can still connect with the emotions and feelings that it evokes.

Overall, the shift in my visual language has allowed me to delve deeper into the emotional and psychological aspects of memory and place, while also making my work more accessible to a wider audience.

Sanjana - I understand where you are coming from. But I want to delve into this idea of accessibility and abstraction a little more. You mentioned something along the lines of how you touch every thread in your artwork; that the making process requires that you feel the entire work. How important is tactility and texture to your practice?

Sabiha - Tactility and texture are absolutely essential to my practice as a textile artist. As you mentioned, I touch every thread in my artwork, and this process of physically handling the materials is a crucial part of my creative process.

For me, weaving is a deeply embodied practice that engages all of my senses. The tactile sensation of the materials as they pass through my fingers, the sound of the shuttle as it glides back and forth, the visual patterns that emerge as the cloth takes shape—all of these elements combine to create a rich and immersive sensory experience.

In terms of the finished work, the texture and tactility of the materials are also an important part of the viewer's experience. My textiles are meant to be felt, to be experienced on a physical level as well as an emotional one. The richness and complexity of the materials—the way that the threads interweave to create a tapestry of texture and colour—is an integral part of the artwork itself.

In many ways, I see my textiles as physical embodiments of memory—each thread a reminder of a particular moment or experience that has been woven together to create something new and beautiful. By engaging with the work on a tactile level, the viewer is able to connect with this sense of embodied memory in a more direct and immediate way.

Sanjana - But how do you choose the material? How does your response to a subject or memory affect it? What is the process after?

Sabiha - The process of weaving involves careful consideration of material choices. The selection of the warp material is crucial, as it determines the number of threads required per inch. When choosing materials, I take into account several factors, including the desired pattern, colour, tactile quality, and malleability of the cloth.

For example, in Crammed between the cracks III, I wanted the work to have a light, airy quality but still have some body. I picked a thin cotton for the warp that allowed for good pattern creation and picked a thicker acrylic yarn for the weft that helped with spacing and adding weight and also giving it a sort of faded appearance.

My response to a subject or memory can also influence the way that I approach the weaving process. Sometimes I will begin with a specific image or idea in mind, and the weaving process becomes a way of translating that image into a tactile form. Other times, I will start with a more intuitive, emotional response to a memory, and allow the materials themselves to guide me in the weaving process.

Once the warp material is selected, calculations are performed to ensure the threads will accommodate the planned pattern. Then, the loom is set up and weaving can begin, with the option to change the weft yarn as the process unfolds. I pay attention to how colours mix on the loom and the resulting effect on the pattern to determine the nature of the weft.

Crammed Between the Cracks III, 2019

Sanjana - Wow! If you hadn't explained that, one would never realise what goes on behind the scenes or even the general time it takes to complete one work. Essentially, weaving is a slow process. So Sabiha,

where are you right now and where do you think you are headed in terms of your practice?

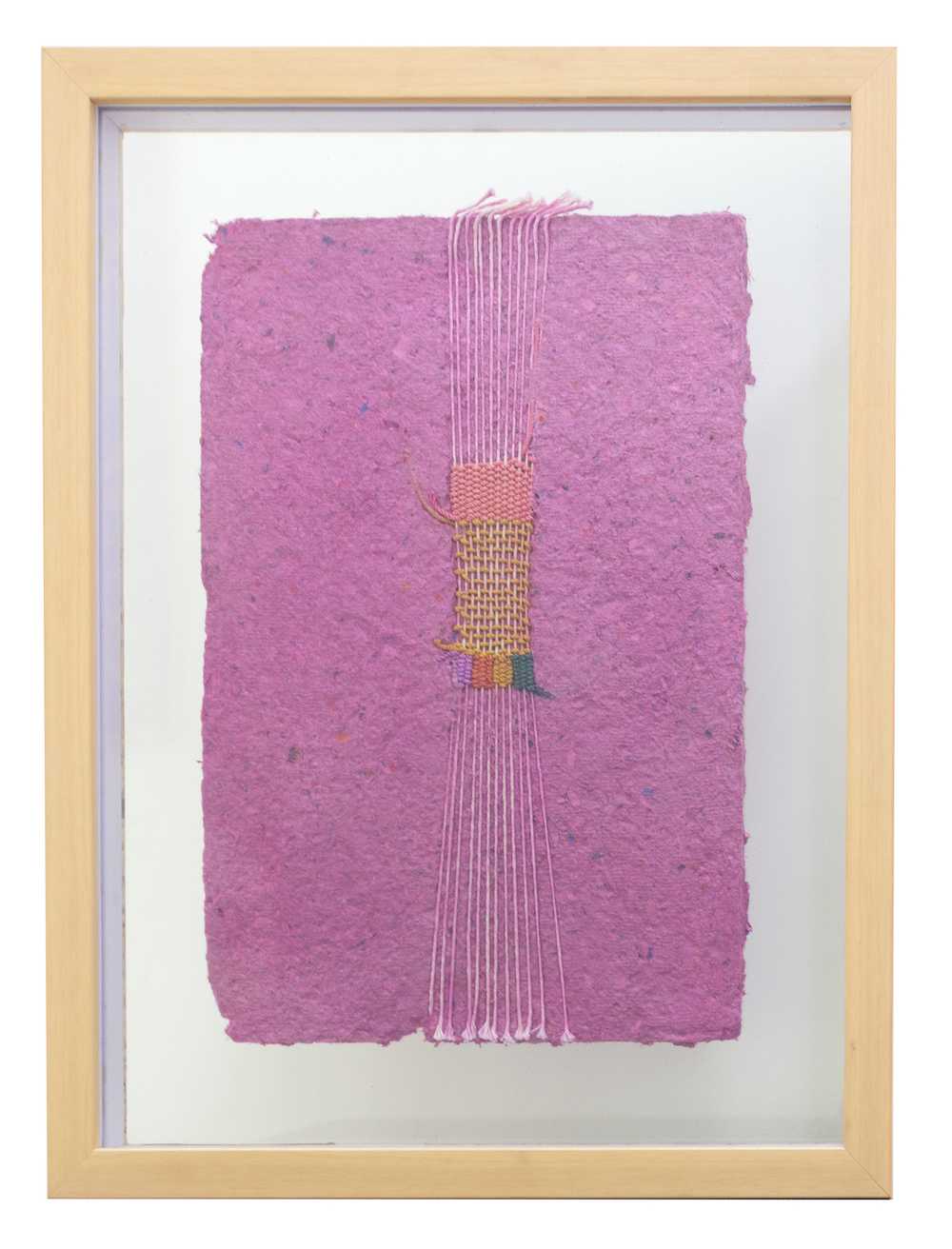

Sabiha - Currently, I am at a pivotal point in my artistic journey where I am experiencing a significant shift in the way I approach my work. I am looking forward to exploring the impact of abstraction on how viewers perceive my artwork. In addition to my exploration of abstraction, I am also delving into a new medium—paper.

Working with paper has been an intriguing experience, as its unique properties and process have required me to approach my work in a different way. I am working towards merging both textile and paper mediums to see what innovative forms and media will emerge from my experimentation and exploration.

Fragments 1.1, 2021

Stitches, 2021

Sanjana - That’s wonderful! Before you go, I want to know one last thing. Whose work are you inspired by?

Sabiha - Some textile artists who have inspired me are Monika Correa, Mrinalini Mukherjee, Nelly Sethna, Faig Ahmed, Sheila Hicks, Anni Albers, Lenore Tawney, El Anatsui, Elana Herzog and Do Ho Suh.

View PERCOLATE on Terrain.art.